Another reason to say no

- Updated: June 28, 2019

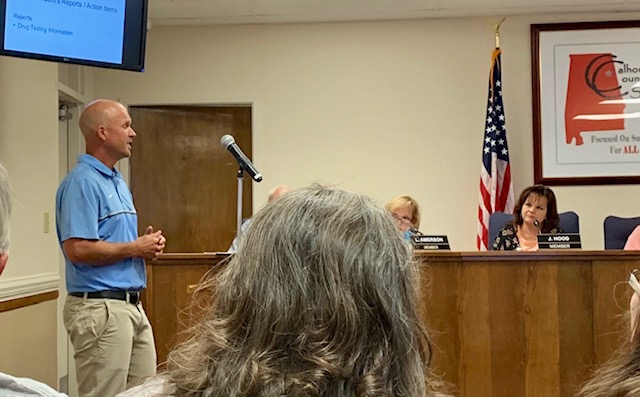

PV coach Hood pitches system-wide drug testing policy to Calhoun County school board

By Al Muskewitz

East Alabama Sports Today

Brad Hood nervously waited his turn to address Thursday night’s Calhoun County school board meeting worrying all the time he might be the controversial speaker of the evening.

Another contentious issue in the meeting took care of those worries so the Pleasant Valley High School girls basketball and state championship-winning cross country coach was a little more relaxed when he approached the board about implementing a student drug testing policy and program system wide.

Hood thought the presentation went “really well;” the board members were attentive, engaging and seemingly receptive to the idea. In his opening remarks he asked whether the issue had ever been brought to light during any of the board members’ terms and the answer surprised him.

Never, he was told. While the county’s student handbook does address drug involvement on school property, it does not spell out a specific testing policy.

“There’s no accountability for the kids, period, not (only) athletes, but kids, period,” Hood told East Alabama Sports Today. “Right now a young kid has no reason to say no other than they know they’re educated (about it) and it’s bad for them.

“There’s not a reason for a lot to say no because it’s not tested. Now we’re trying to give them a reason to say no.”

The board took no action other than give its blessing for Hood to form an independent committee to look into funding options and the policies and procedures for the actual testing. Hood said he hoped to have a committee formed and a game plan ready by the July board meeting.

If a policy is adopted it would cover the schools in the Calhoun County system, which includes the high schools of Alexandria, Ohatchee, Pleasant Valley, Saks, Weaver, Wellborn and White Plains.

School systems in neighboring Etowah, Talladega and St. Clair County counties, as well as the Birmingham metro, have testing policies. The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention said about 18 percent of public high schools nationwide have a mandatory drug testing policy.

Both Hood and Pleasant Valley football coach Jonathan Nix emphasized the impetus of the testing program is more awareness than punitive – although there will be consequences for positive results – and not driven by any perceived competitive advantage an opponent school may be getting by artificial means.

“This is not anything to do with somebody on steroids or something like that trying to get an advantage,” said Nix, who was part of St. Clair County’s policy committee when he coached at Ragland. “I think we’re solely attacking it from the end of getting kids to not get into those gateway drugs.”

While athletes will be the most visible constituency in the testing program, the testing will be undertaken across the board. In the St. Clair County program, for example, a random testing sample includes 10 percent of the athlete population, 10 percent of participants in other extra-curricular activities (FFA, band, etc.) and anyone in possession of a school parking permit; the model is similar nationwide.

Under that model, the only groups that could potentially avoid being tested would be those who ride with someone to school or take the school bus.

“Now, nobody’s going to know until they catch them in the act and we can’t do anything unless we catch them in the act,” Hood said. “It’s a problem. If we don’t (address it) we’re naïve and we’re turning a blind eye.”

When asking about the legal liability for such a program the board was told it was a “no-brainer,” that there was actually less liability because they were ensuring the safety of the athlete or student.

There are federal grants available to fund such programs, but some schools handle it in-house. One school in Jackson County self-funds its athletics drug-testing program; swabs that test for up to 15 different substances are $6 each and the school does “three or four” tests a week. If a test returns positive, the athlete’s parents have 24 hours to produce a more detailed report at their own expense and the athlete doesn’t practice or play until it is.

It was suggested some coaches might not like the policy because it could cost a team a star player before a big game to which board member Michael Webb reportedly said “if we have any coaches in our county who are opposed to this they need to work in another county.” Board president Tobi Burt said “if this saves one child’s life the whole process is worth it.”

Nix believes the program implemented in St. Clair County was “very effective” as a deterrent.

“It gave a kid a reason to say no,” he said. “Everybody’s got different motivations of why they’re doing this, but to me the main reason was leaders there wanted to give a kid a chance to say no to putting bad stuff in their body.

“We all think about how many reasons can we give our kids nowadays to make good choices. There’s so much instant gratification these days. One bad decision can set the course for a life to go in a different direction. To me, we’re trying to look after kids. We got in the business to take care of kids and nowadays kids need more of a reason to say no to that stuff.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login